Learning Objectives

This blog post seeks to furnish you with a foundational comprehension of work-stress and practical methods to mitigate its prevalence. The following aspects are included:

- Consider the various elements that lead to work-stress, reflecting on both individual and organisational perspectives;

- Think about the signs of stress and their cumulative effects on overall well-being;

- Identify the different sources of stress within the workplace, allowing for thoughtful consideration of how to address these factors in personally and socially meaningful ways;

- Reflect on how elevated stress levels can adversely impact focus and performance, resulting in a higher likelihood of errors and workplace incidents;

- Encourage you to implement strategies for stress management to sustain optimal performance and minimise accident risks;

- Grasp broader organisational factors, such as leadership deficiencies, inflexible cultures, and inadequate support systems, and their roles in contributing to work-stress;

- Understand how the physical and cultural environments of workplaces can intensify stress levels; and,

- Support you to embrace more flexible, supportive, and adaptive practices that can help reduce employee stress.

Topics Covered

This blog post looks at how to understand and reduce work-stress. The post includes the following topics:

15 Contributors to Work-Stress

The factors contributing to stress are complex and varied, encompassing both individual elements such as workload and interpersonal conflicts, as well as environmental influences like inadequate management and insufficient resources. Stressors can accumulate and affect overall well-being.

Work-Stress: Slips and Mistakes, Accidents

Stress may contribute to your decreased concentration, increased errors, and even workplace accidents.

Work-Stress: Organisational and Environmental Contexts

There are broader organisational and environmental factors that contribute to stress, such as gaps in leadership, rigid cultures, or insufficient support systems.

Work-Stress Reduction: From Strategies to Benefits

Various stress reduction strategies, range from mindfulness, time management, physical activity, to seeking professional help.

WORK-STRESS REDUCTION: OPTIMISING SAFETY PROCEDURES AND AWARENESS

You and others can benefit from health optimisation to decrease turnover and improve morale.

9 Steps to Work-Stress Reduction

When experiencing discomfort, you can effectively navigate intense emotions by recognising stressors, establishing boundaries, enhancing communication, and leveraging support services.

15 Contributors to Work-Stress

For example, these include the following.

- High workloads and inadequate support;

- Illness or death and loss of family and friends;

- Personal history of trauma and lack of caring for one’s self;

- Career damaging to admit traumatic stress;

- Lack of agency and compassion fatigue;

- Social pressure to remain at work;

- Lack of acknowledgement for work undertaken;

- Violence at the workplace;

- Isolation;

- Inadequate employee assistance programs;

- Commercialism and unstable funding;

- Maintaining currency of work-based knowledge;

- Legal claims;

- Similarly inadequate public knowledge about emotional, forensic, social, and medical challenges; and,

- Slips and mistakes. Let us explore in more detail certain contexts where inaccuracies related to work can arise.

Work-Stress: Slips and Mistakes

Work-induced stress or trauma affecting the health, aviation and maritime industries is influenced by a variety of factors. When workers make errors they often undergo stress (Farnese, et. al., 2022). Examples of work inaccuracies include slips, and mistakes. Mistakes occur, for example, when workloads become overwhelming, stress is present, and sleep is inadequate (Alyaha, et al., 2021). Moreover, mistakes happen with poorly functioning and designed systems (Wilf-Miron, et al., 2003). People ranging from individuals to organisations can benefit from assistance in dealing with work-stress.

Organisational aspects could enhance, diminish, or have other effects on human performance. For instance, take into account the aviation industry and aircraft. It is worth noting that a significant percentage of aviation accidents, ranging from 60% to 80%, can be attributed, at least partially, to human error (Shappell et al., 2007, p. 228). Hopcraft and Martin (2018) pointed out that the aviation sector is more advanced in cybersecurity compared to the maritime industry. In general, a compromised cybersecurity system could lead to a work-based environment prone to accidents.

Reason (1990, 2008), Rasmussen (1986) and Raicu, et al. (2019) have provided an analysis of peoples’ errors, particularly in the context of aviation and other scenarios. These errors are often attributed to the limitations of human cognition, including a lack of focus and the constraints of temporary memory. Cushing (1994) linked aviation crashes to misinterpretations between workers on the ground and those in the air. These shortfalls or human conditions contribute to work-stress. Reason’s framework outlines three types of errors:

1. Work-Stress and Skill-Based Slips

Skill-based slips occur when behaviour deviates from peoples’ intentions due to failures in execution or storage, such as when a crew becomes fixated on a warning light and fails to recognise the aircraft’s difficulties.

2. Work-Stress and Rule-Based Mistakes

Rule-based errors involve correctly identifying a problem but applying an incorrect solution, while knowledge-based mistakes occur when people lack the necessary knowledge to select the appropriate course of action.

3. Work-Stress and Knowledge-Based Mistakes

Knowledge-based errors occur when a person lacks the knowledge to choose the appropriate course of action.

Errors can stem from factors unrelated to individual human error, such as environmental conditions, organisational issues, and personnel or human factors. Shappell et al. (2007) suggested that commercial aviation accidents involve different levels and factors beyond human error. Shappell and Wiegman (2000) expanded upon Reason’s (1990) Swiss Cheese Model by introducing a system that categorises errors into four levels:

1. Organisational influences.

2. Unsafe supervision (which is a component of organisational factors).

3. Preconditions for dangerous acts (also falling under environmental factors).

4. Unsafe acts (or issues related to personnel).

The error classification levels in this system are:

(a) organisational influences;

(b) unsafe supervision (considered part of organisational factors);

(c) preconditions for dangerous acts (categorised as environmental factors);

(d) unsafe acts (or personnel-related matters).

An instance of organisational influence could involve resource management (a management aspect). Unsafe supervision would occur if a known issue is not addressed (a supervision aspect). Preconditions for dangerous acts could impact the physical environment (a physical environment aspect). For example, when workers become reckless and disregard safety protocols; it can contribute to serious accidents or injuries. Lastly, unsafe acts encompass both errors and violations (knowledge and skills aspects) contributing to work-stress.

Accidents: Organisational and Environmental Contexts

The primary causes of accidents might be attributed to the aircrew and their surroundings. For example, individual errors made by operators and the circumstances that lead to these errors, rather than lack of supervision or organisational elements (p. 231). On the other hand, workers may discover themselves in a dysfunctional organisation and could be required to exert significant efforts to implement changes even gradual ones.

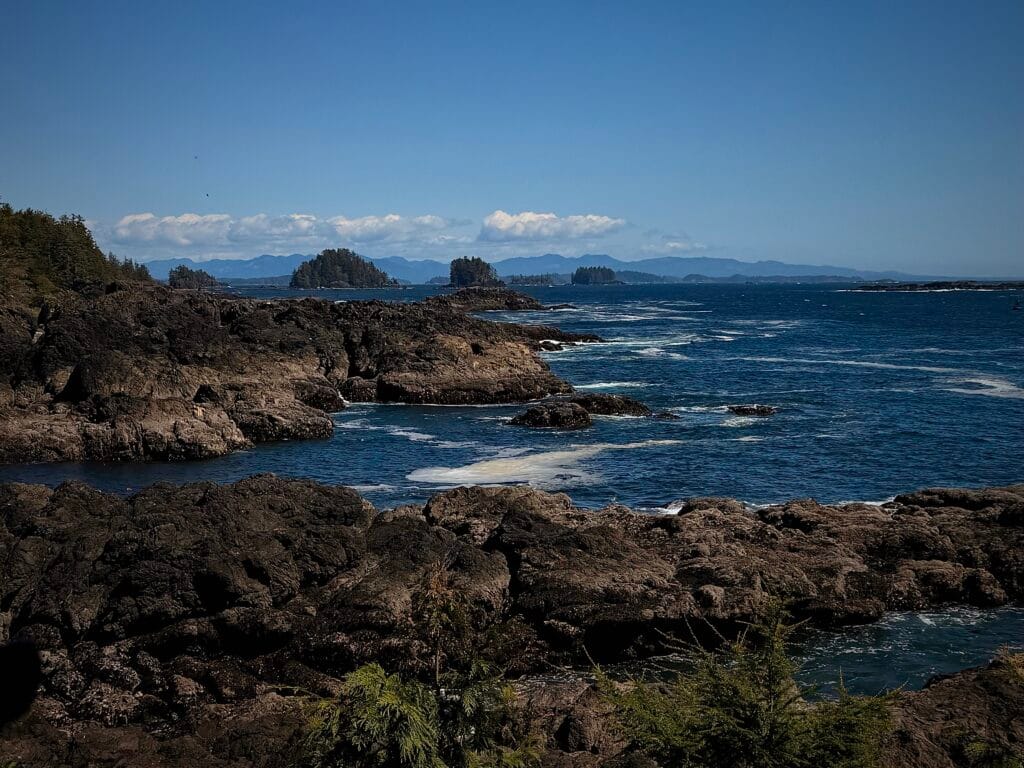

Engage in mindfulness practices to stay present in the moment and envision the tranquility of a natural setting.

Work-Stress Reduction: From Strategies to Benefits

Work-Stress reduction involves implementing strategies and techniques aimed at decreasing stress levels. As a result, there are multiple methods that can be utilised, including enhancing work structure, promoting effective communication, providing worker assistance programs, and cultivating a favourable work atmosphere. Moreover, techniques like mindfulness training, time management, coaching, ergonomic adjustments, and promoting a better work-life balance can also contribute to stress reduction. Afterwards, the benefits of effectively reducing stress in the workplace include improved worker health, increased work satisfaction, and higher productivity. Eventually, employers often implement these strategies to create a more harmonious and efficient workplace for their workers.

At work, you might encounter stress and find yourself questioning your work performance as well as your professional identity. Furthermore, this situation could be linked to a sense of uncertainty regarding your personal effectiveness and a deficiency in coping strategies to manage stress.

Work-Stress: takes its toll on employers, employees, and broadly their families’ mental and physical health, and it is often a critical topic for your place of employment.

Work-Stress Reduction: Are you experiencing distress in your workplace? For this reason, it may be beneficial to explore methods of reducing stress in your work environment.

WORK-STRESS REDUCTION: OPTIMISING SAFETY PROCEDURES AND AWARENESS

The aviation industry’s safety protocols and awareness initiatives can provide valuable insights for the healthcare sector. (Wilf-Miron, et al., 2003). Additionally, understanding work-stress and mistakes in the healthcare field can offer valuable insights for various other sectors, including aviation and maritime. For instance, pharmacists may face significant pressure to perform at their best and prevent mistakes (Balayssac, et al., 2017).

9 Steps to Work-Stress Reduction

You have the option to enact one or multiple of the subsequent actions.

- Consult legislation, regulations, and case law;

- Access educational support to understand health policies, practices, and the regulatory environment;

- Solicit and develop work-stress and social supports;

- Access mediation and counselling support;

- Maintain personal care, eating, sleeping, and living well;

- Develop a balance between work and your own life;

- Seek out organisational support; and,

- Finally, use humour and be hopeful.

Meanwhile, your challenging work environments can lead to you experiencing stress, engaging in self-harm, aging prematurely, and becoming a target of victimisation. Read about other stress reduction strategies at A Resiliency Toolkit.

In Closing

Eventually discover the multitude of options available to alleviate your work-stress or trauma. Furthermore, consider the psychological, medical, social, and cultural factors that contribute to this stress or trauma. To counteract it, make sure to unwind both before and after work. Engage in a range of activities, such as exercising, spending quality time with loved ones, socialising, or taking day trips or even vacations.

This blog post explored the following.

- 15 factors contributing to stress;

- Occupational stress: errors and oversights;

- Incidents in organisational and environmental settings;

- Mitigating work-stress: from approaches to advantages;

- 9 steps for reducing work-stress; and,

How to contact us.

References

A-F

Alyahya, M.S., Hijazi, H., Alolayyan, M.N., Ajayneh, F.J., Khader, Y.S. & Ai-Sheyab, N.A. (2021). The Association Between Cognitive Medical Errors and Their Contributing Organizational and Individual Factors. Risk Management and Health Care Policy, 14.

Dove Press.

Balayssac, D., Pereira, B., Virot, J., Lambert, C., Collin, A. & Alpine, D., Gagnaire, J-M., Authier, N., Cuny, D. & Vennat, B (2017, October 26). Work-related stress, associated comorbidities and stress causes in French community pharmacies: a nationwide cross-sectional study. PeerJ 5. National Library of Medicine.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29085764/

Cushing, S. (1994, February). Fatal Words: Communication Clashes and Aircraft Crashes. Technical Communication, 42 (1).

https://press.uchicago.edu/ucp/books/book/chicago/F/bo3633901.html

Farnese, M.L., Fida, R. & Piccolo, M. (2022, February). Error orientation at work: Dimensionality and relationships with errors and organizational cultural factors. Current Psychology, 41 (2).

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s12144-020-00639-x

H-W

Hopcraft, R. & Martin, K. M. (2018). Effective maritime cybersecurity regulation – the case for cybercode. Journal of Indian Ocean Region, 14 (3), 354-366.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/19480881.2018.1519056

Raicu, G., Hanzu-Pazara, R. Zagan. R. (2019). The impact of human behaviour on cyber security of the maritime systems. Advanced Engineering Forum, 34, 267-274.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.4028/www.scientific.net/AEF.34.267

Rasmussen, J. (1986). Information processing and human-machine interaction: An approach to cognitive engineering. Wiley.

Reason, J. (1990). Human error. Cambridge University Press.

Reason, J. (2008). The human contribution: Unsafe acts, accidents and heroic recoveries. CRC Press, Taylor & Francis.

https://www.taylorfrancis.com/books/mono/10.1201/9781315239125/human-contribution-james-reasonb

Shappell, S., Detwiler, C., Holcomb, K., Hackworth, C. Boquet, A. & Wiegmann, D. A. (2007). Human error and commercial aviation accidents: An analysis using the human factors analysis and classification system. Human Factors, 49 (2), 227–242. Sage.

https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1518/001872007X312469

Shappell, S. A., & Wiegmann, D. A. (2000). The Human Factors Analysis and Classification System – HFACS: Final Report. Office of Aviation Medicine, Federal Aviation Administration.

https://commons.erau.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1777&context=publication

Wilf-Miron, R., Lewenhoff, I. Benjamin, Z. & Aviram, A. (2003). From aviation to medicine: applying concepts of aviation safety to risk management in ambulatory care. (Learning from Other Industries). Quality and Safety in Health Care, 12 (1).